Atlantic

Conquest

A highway across indigenous territories is the first phase of an extractivist project that threatens one of the last primary forest reserves in the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor. Pressure on land, Panama Papers and ancestral resistance. How is it a Dutch businessman is about to achieve what even Christopher Columbus could not?

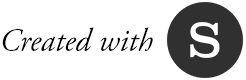

The defeat of Columbus

1502

Christopher Columbus' fourth and final voyage to the Americas. Four sailing ships and140 crew. They took two months to cross the Atlantic. The Caribbean received them with hurricane winds and sixteen-foot waves. They found refuge in the archipelago we now call Bocas del Toro, in western Panama. Columbus was fascinated with this immense and serene bay, full of dolphins. He baptized it in his name: Admiral Bay, and the principal island, Colón. They were looking for a path to the Pacific.

The indigenous people of the area arrived in canoes with fruits and gifts. But the Spanish only had eyes for the plates of gold they wore as necklaces. They asked the people where they found it. They answered that about a two day sail to the west, there was “infinite gold”. The Ngäbe and Buglé called this place Veraguas.

The Europeans pointed their prow east and later founded a settlement at the mouth of a river they baptized Belén. They convinced the indigenous to take them to their mines. Immediately upon entering the forest they saw bright stones in the roots of the trees. They found gold simply by running their hands through the earth. Columbus wrote to the King of Spain,

“I have seen more gold in two days in Veraguas than in two years in La Española-Dominican Republic”.

The Conquistadors moved to attack and captured the chief. While they transferred him in a boat, hands and feet tied, he managed to launch himself into the river and survive. Immediately, he organized his men for a counterattack and at arrow point forced the invaders to return to the sea. Henceforth was born the myth of “infinite gold” that has remained alive, centuries upon centuries, to this day.

515 years after the arrival of Columbus, a silent, yet expanding operation now threatens the existence of dozens of communities in one of the last lungs of primary rainforest of Panama— the Mesoamerican BiologicalCorridor. A massive infrastructure project that includes miles of new roads, hydroelectric, mega-mining, a network of electric power transmission lines and associated groundwork in protected forests. These projects are anchored by nineteen miles of asphalt that will connect the Panamerican Highway with the Caribbean sea. It is a project that the Panama government has baptized, with the sensibility of a stone, “The Conquest of the Atlantic”.

Opening the road

The road being opened through the mountains of Veraguas was planned in the mid 1970s, during the regime of General Omar Torrijos.

The commander of a country occupied by United States military bases and cut in two by a canal that was not theirs, Torrijos thought these mountains would feed the national riches. These were not the times of climate change or environmental apocalypse. Deforestation was not a suicidal decision, but one of hope: the expansion of the agricultural frontier could be the engine of development.

Torrijos tried several times but without luck. Torrijos founded Romero City, on the banks of the Belén River, where hundreds of Salvadoran farmers had arrived to escape from their civil war. He hoped they would work the land. The city prospered. At the end of the armed conflict in El Salvador, they returned to their country and left a ghost town. Torrijos also founded a work camp in Coclesito where urban youth came to carry out social works.

Torrijos, fascinated, constantly visited these lands and there he encountered his own death, in 1981, when the small plane in which he traveled crashed against a crag near North Coclé.

The project was left in limbo.

In the mid 1980s, discussions around indigenous autonomy of the territory intensified. In Panama there are seven native groups. Two of them, the Ngäbe and Buglé, with close to 350,000 people, eight percent of the Panamanian population, inhabit these lands. According to the archaeologist Richard Cook they have been there for more than 10,000 years. Panama’s Administration agreed to their claims on the land, and in the case of the Ngäbe and Buglé, decided their reservation lands ended at the Calovébora River. Along it river valley, Torrijos had planned the road. They recognized Ngäbe and Buglé land in Bocas del Toro, but not in Veraguas. They were left the extremely rugged infertile lands susceptible to flooding. In this way, a great many of the native communities were excluded from the Ngäbe Buglé Reservation.

According to the last national census, 63% of the indigenous peoples of Panama live outside of the legally constituted reservations, 76% live without electricity and one in every two live in extreme poverty.

In 1997, after the US invasion, the government of Ernesto Pérez Balladares approved the opening of a gold mine, Petaquilla, in the district of Donoso, the same area Christopher Columbus had visited.

The gaze of the country again fell upon these lands. Then in 2004 the son of General Torrijos, Martin, ascended to the presidency and decided to restart his father’s old project. This was the beginning of the first phase of the road, between Santa Fe and Gtabal. Despite the route cutting through SantaFe National Park, it was approved.

Construction on the second phase, the most critical one, began in 2014 and is now 40% complete. When complete, it will stretch 21 miles through the jungle and diverse indigenous communities and will consolidate a road corridor from the Panamerican highway to the Caribbean sea. It is the opening of a project that will exploit natural resources at a terrifying scale: mega-mining, hydroelectrics, new transmission lines, roads and mass tourism. A devastating combination in a country sensitive to climate change. The indigenous communities, though, have been told them it is a social project that will improve their links to the greater world.

The work, bid out in 2014 for u$s 37 million, was awarded to three companies who are working together —Transeq, Concor and Itecpa— to carry the project forward. Without much experience in public works, these companies are now flourishing since 2014, when the Panameñista political party came to power.

"The new road has been yearned for decades, and today it has become a reality", says the Ministry of Public Works spokesperson Minerva Bethancourth. "The work is progressing despite the inclement weather and it is expected that the machinery will have reached the sea by the middle of January 2018, more than an environmental strategy, it is about compliance with the legislation, this project has no irreversible impacts."

The Ministry of Environment of Panama authorized the Environmental Impact Study that permits the advance of heavy machinery over primary tropical forests and permits the companies to extract materials in these same mountains. So they are blowing up hills with dynamite and constructing immense quarries alongside of rivers that extract stone from the riverside to grind them into gravel.

One of the largest quarries runs along the Luis River, where heavy trucks come and go through an entrance guarded day and night by security personnel. The river, which is the primary source of drinking water for the communities, has become the color of chocolate. The daily newspaper, El Siglo, reported months ago about the children affected with diarrhea, and stomach pains by drinking the water from nearby streams. The Public Defenders office opened an investigation. “I think the road will bring good things and bad things”, says Mariela, a young Buglé, while breastfeeding her children in a small shack of wood and palm at the border of what will be the road. She has a small fire lit on which she cooks plantain soup. “The good things will be for those from outside and the bad things for us”, she affirms.

“They came here and told us that they are doing this for the poor. But if we don’t have the money to pay for transportation nobody will take us anywhere”.

Ancestral resistance

The Caribbean writer Franz Fannon, author of 'Los condenados de la tierra', speaks of the zone of “no-being” to explain the place western society gives to indigenous peoples: a hazy space of individuals without faces nor rights who always can be displaced in the name of progress.

The Panamanian economy, which has seen the greatest growth in Latin America over the last decade, maintains one of the highest levels of inequality in the world: Panamá ranked in 10th position, World Bank announced last January. Within this context of inequality, native communities are especially marginalized. The UN Atlas of Human Development shows that Panama invests $480 per inhabitant per year,however that investment is lower for indigenous peoples at $200 per person per year.

From Panama City, the forests of the interior of the country are considered inhospitable lands, uninhabited and wild. Jungle waiting to be developed. It’s as if there are two worlds—one place for people to live, and another that is virgin nature. But in the mountains north of Santa Fe of Veraguas live about 20,000 people, the majority indigenous and farmers. Without electricity, without running water, without sewers, they live a pre-modern life. There is no division between human and nature. For them, the forest is life-space not an opportunity for business. They live off the land,collecting fruits, fishing the rivers, and planting small parcels that are left fallow every five years to allow for the regeneration of the land.

These people barely handle money. They only see cash when they work as day laborers —at $5 a day— or when they receive assistance from the State. The communication between communities takes place on small muddy trails through the enclosed jungle. They walk hours to arrive at a meager health center; the nearest hospitals much farther away. They only go there for emergencies. Most children are born at home and shamanic medicine is more common than mainstream medicine.

The remoteness of this landscape, has buffered these indigenous peoples from the growing trend of development and tourism that that dominates Panama. Their isolation is what has saved their forests from exploitation and permitted them to maintain the thread that connects their way of life with ancestral times. Until now.

Five hundred years on, the Conquest returns.

"We want a kind of development that includes us and respects nature. We are not against progress. We use cell phones, Facebook. But we want our way of life to be respected ".

These mountains are the last refuge of primary forests in a country which in the last 80 years has lost 65% of its forest cover, according to the Smithsonian Institute environmentalist Stanley Heckadon in his current documentary, “Cuando vuelvan los Bosques” —“When the Forests Return”—. History teaches us that every time access is opened to these types of zones, after the road comes massive deforestation.

“To take care of nature is to take care of oneself. It is the only way to survive”, explains Cristina, who lives near the road.

Chief Saturnino Rodriquez, leader of the community congresses of the area, offers us hot Pixbae, an exquisite fruit abundant at this time of year. What keeps the chief awake at night are the consequences of opening the road. “Once they cut the road, they will come for the territory. It is only a question of time”.

Rodriguez lives in the community of Playita, on the border of the Calovébora River, in a house like the rest of the indigenous. With wooden walls, thatched roof and just two rooms. Elevated floors are used to protect them from floods and snakes. At night, in front of the fire, the elders enthrall the children, with long poems that retell the arrival of Columbus, their expulsion and the epic of their people.

“In our cosmovision, man does not own the earth. We both need each other. The forests give us our sustenance and we are its guardians for the next generations”. The chief is supported by international statistics. A landmark study published last year by Rights and Resources Initiative showed that indigenous people manage more than 24 percent of the total carbon stored in the canopy of the world’s tropical forests. In Panama, 50% of these forests are indigenous reservations, although they only make up 17% of the national territory, according to the United Nations Program for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (ONU-REDD). If you add to this the untitled collective lands of Panama’s indigenous, the area of indigenous land is even greater.

According to these statistics it is much more effective to legalize indigenous lands than to create protected areas. Maybe for this reason, the Canadian scholar, award-winning filmmaker and environmental activist David Suzuki believes the path to reversing climate change will not be led by environmentalists, but instead by indigenous peoples. That is to say, the future of humanity will be indigenous, or it will not be. They are on the front lines of the battle with sticks and stones up against armies and transnational companies. In 2017 alone, thirty indigenous leaders died violent deaths worldwide, according to a last September report by Climate Home.

Indigenous communities practice a high form of direct democracy. They make decisions by consensus. The decolonization philosopher and creator of liberation philosophy, Enrique Dussel, in his “20 Tesis en Teoría Política”, clearly explains it.

“Rigoberta Menchu and the Zapatista Liberation Army make a distinction between two forms of leadership when they say that western leaders lead by ordering while indigenous leaders lead by obeying”.

This strength in their internal lives could turn out to be a weakness as they face the advance of western civilization. However, Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, Latin American historian at McGill University affirms that we just need to wait. “It is shown that when the moment arrives, the indigenous sustain the longest fights. There is much greater cohesion and more solid support for their leadership. Divisive tactics do not work”, he explains.

Hungry

for land

The communities continue asking for annexation of their territory by the Ngäbe Buglé reservation. Or at least, recognition of the collective use of their land. For centuries, they have moved freely in these mountains, an internal migration that nobody has ever restricted.

“The government, what it wants is title our lands individually. A little farm for every family. After, the speculators will come and buy us up, one by one. We ask for the recognition of the collective use of the land”

ANATI –The National Authority for Land Administration– recognizes what they call “possession rights”. They are informal titles that in theory grants the right to register the land to those who work it and have lived on it for at least five years. But many people do not understand how to do out the paper work required to register their land. This system has helped hundreds of humble subsistence farmers, but has also allowed lawyers of politically connected real estate developers to title tens of thousands of acres of lands at bargain prices. By permitting the commercialization of possession rights, entrepreneurs from the city come to the communities with their lawyers and institutional contacts, acquire the land rights at ridiculously low prices prices and re-title them in their name. Legally titled, the price of the land triples automatically. And so begins the feast of land speculation.

Months ago, representatives of the indigenous communities went to Santiago, the capital of Veraguas, to find out the status of their lands. They saved money for many weeks in order to afford the travel costs. On foot, by canoe, and later by bus, they ultimately arrived at the city’s ANATI offices. However, the ANATI employees made them wait all day and did not attend to them. “Stay calm, nothing will happen with your lands, all is as it has always been”, a secretary told them. As they arrived, so they returned.

While ANATI representatives appeared unable to meet with indigenous leaders, they have been able to help provincial political leaders with their land issues. Such as Pedro Miguel González, honorable deputy of the National Assembly, representative of Sante Fe, Veraguas, for the Democratic Revolutionary (PRD) political party. On March 24, 2017 he titled 49.5 acres on Tute Mountain en Santa Fe, Veraguas. He paid $138 dollars for the whole lot.

González assures that there is no illegality. "This was a property of the family and we just changed the category of ownership over property title". He explains that the land is used by as an agricultural farm. "It should have been issued as belonging to all siblings, this is a pending procedure", he concluded.

Gonzalez has a tumultuous record: he was accused of killing the US military Zak Hernandez in June 1992, a day before the visit of the ex president George Bush. Although he was acquitted of the crime in Panama, he is considered a fugitive from justice in the United States.

It is these types of situations that the indigenous inhabitants want to avoid: that their forests are transformed into the private estates of the multi-millionaires of Panama city. Such as that of Ramón Fonseca Mora, the disgraced celebrity lawyer who through his firm Mossack Fonseca helped launder and hide money generated by the corruption of half the world. After the blockbuster Panama Papers scandal, a knockout blow to the reputation of the country, Fonseca retired to his farm where he now passes the time managing his plantation of oranges, the juiciest of Panama.

The chief Saturnino says that the pressure on their land keeps growing, especially in the mouth of the river at the Atlantic, where the road and river come together.

The community of Calvébora is the best kept secret of the Caribbean: an oasis of blue sky, white sand beaches and emerald green sea. The last virgin beaches of Panama.

Approximately 2000 people live in Calovébora. The population is more heterogeneous than in the mountains: there are subsistence farmers, who are indigenous, and Afro-descendants, mostly fishermen. They live in isolation and, for this reason, celebrate the coming of the road. Many are happy to sell their land.

“When the speculators arrive, they talk of a thousand, two thousand dollars, and my people think they will be millionaires. I tell them they do not need to sell. That we, without land, we cannot survive. It will be a very difficult fight”

Contrary to the indigenous communities, they believe that selling will take them out of poverty. The people live according to the rhythm of nature. Only a few houses have solar energy. Since cars cannot reach them, there are no streets. There is complete tranquility. The only visitors are the evangelical preachers, the narco-traffickers on their way to the United States and the police that pursue them. And, recently, foreign investors. Pioneers. The new Conquistadors.

Max Van Rijswijk is one of them.

In Calovébora, they describe him as a Dutchman with a Viking profile. Blonde and almost six and a half feet tall, he arrived in Panama in 2003 and introduced himself as an environmental activist focused on preservation. Soon after he arrived, he created foundations with these goals: protect the turtles, save the rainforests, prevent progress from destroying the nature of Panama. He arrived in Calovébora offering the subsistence farmers land transfer agreements to create immense animal reserves. He was particularly interested in one type of property: coastal beaches that lie at the mouth of the rivers.

Between 2007 and 2017 he acquired the titles to 6,650 acres along 7.5 miles of the the Caribbean coast –2,075 acres in Donoso and 3,526 acres on the coast of Veraguas– that are now on sale online for millions of dollars through his company Caribbean Riviera. On the internet, one can find his company’s portfolio:

“The Caribbean Coast of Panama is still undervalued compared with other beach destinations such as in Costa Rica, Mexico and the Dominican Republic. With the incredible investment in infrastructure taking place right now, united with the growing attraction that Panama reflects as an emerging investment destination, it is predicted that prices will double in the next three to four years. This is the optimal time to buy one or various shown properties in order to generate an investment that you expect, with high return and relatively low risk in a short to medium term horizon”.

Over the years, Van Rijswijk has organized an intricate network of foundations, limited liability companies, and hired an army of lawyers who have given the legal cover to his network of shady investments. How did Max Van Rijswijk, in ten years, convert himself into a tropical land baron, becoming the owner and master of the lands that even Columbus couldn’t conquer?

The barbaric coast

To get to the house of Paulino González Sianca, you must take a one hour boat from Calovébora. From the water, you can see everything: there are small beaches, like little coves between rock walls that open to the sea. There are broad open beaches. There are beaches with waves to surf and inlets of water so crystal clear that you can see the coral and fish. There are immense arches of stone and submarine caves.

An hour later, you arrive at the mouth of the Estero Salado River. The sway of the waves peters out and the quiet of the river absorbs everything. The forest canopy creates an arch over the water. You arrive at a place where the river is so low that it can no longer be navigated by boat. The property is still 650 feet away, through the water, then up and over a small hill. There are two elevated wood houses where González lives with his children and grandchildren. Children are running around, baskets filled with the day’s harvest.

The man, 80 years old, considers himself victim of fraud, but he has a hard time explaining it all. He was born near here and has lived his whole life in the countryside. He never went to school, and cannot read or write. He says he met Van Rijswijk in the middle of 2008. The Dutchman had arrived in a helicopter and offered him a hundred thousand dollars for all of the beach on his land. González had possession rights and had lived there for forty years.

Van Rijswijk told him that if he accepted, he would need to take care of the entire process at once. They would fly him to Panama City in a helicopter, where he would sign the papers and take care of the payment. Paulino did not know much about the capital. He had only been there once, at a hospital, on the edge of death. This was 30 years ago. However, after speaking with his family, he decided to sell. To them, the beach had no value. They are not fishermen and the sand does not produce food, except for the coconuts. The fertile land that they work daily is upriver; they did not sell that.

The next day, the helicopter arrived looking for him. Paulino went with his grandson. There was a problem during lift off, and the helicopter fell back to the earth. It almost killed them. Instead they travelled by land to Santiago city, and from there to Panama city. They were put up in a hotel in the downtown. They went to the offices of Van Rijswijk and signed the contract. Since he did not know how to read or write, Paulino signed with his thumbprint. His grandson, who could read, was the sworn witness.

The contract included an arbitration clause against Paulino which stated that if he did not follow through with the deal, he would owe Van Rijswijk a million dollars.

They returned to Santiago with a check for u$s 20 thousand dollars as a down payment. They went to the bank. José Gilberto Guardia Pinzón, the Dutchman’s representative, cashed it for them. He gave them half and kept the other half. After using the $10,000 that they received to buy equipment for the farm, clothing, and tools, they returned to Calovébora. Van Rijswijk was supposed to arrive soon after to pay them the rest. He never did. However, on September 22, 2008, the Department of Rural Catastro titled the lands in the name of one of his companies, Veraguas Eco Turismo, SA. Today, these lands are for sale for millions of dollars.

Despite the fact that the Dutch businessman said he was friends with Paulino, he received bad news weeks ago, by the end of November: Paulino went to court against him.

This fraudulent business scheme was used multiple times to trick the community. Mrs. Margarita Pineda Rodriguez suffered the same fate as Paulino. Van Rijswijk came to her house and told her that he was ready to invest in the community, that he would create a reserve to protect turtles. He offered her what seemed like a fortune: $125,000 for 44.5 acres of beach. Dídimo, her son, who had studied in Santiago, told her it was a good opportunity, one that would allow them to re-invest in the farm they had inherited from his grandfather. It would be land without beachfront, but workable land. They talked amongst themselves, and eventually decided to sell. The Dutchman answered that if they wanted to make the deal, they had to travel immediately to the city. Margarita had no shoes. They didn’t give her time to change her clothes. Neither of them knew the city.

“In the city we will buy you shoes, which ever you want”, and thus they traveled. A hotel, dinner, an office, an elegant blonde man that spoke another language. They signed. They received their down payment and returned to Calovébora. Van Rijswijk never returned with his indebted payment. Their land no longer belongs to them and none of they money they were given is left. In one way, though, Van Rijswijk’s team fulfilled their promises: after signing the contract, they bought her shoes.

The most grave case, however, is that of Florentino González. He had lived for more than five years on the beach, at the mouth of the Estero Salado River. Hearing rumors about the presence of developers in the area, he decided to put the land in his name. To his surprise, upon arriving at ANATI, he learned that his land had already been titled by Max Van Rijswijk. Twenty nine and a half acres with two immense white sand beaches.

Florentino got a lawyer and filed for a restraining order. The law was on their side. The lawyer took a surveyor to the area and they realized that the title was obviously fraudulent: the photos that accompanied the documents presented by the Dutchman did not correspond with the place, and the limits of the lot were not real. ANATI had apparently given Van Rijswijk title to the sea bed, something explicitly prohibited in Panamanian law. Florentino reported him to the legal system. Weeks later, Van Rijswijk arrived at the beach with four bodyguards while Gonzalez was away. González is sure it was they who knocked down the walls of his house, and as if that wasn’t enough, left him a memento: six gunshot holes in the laundry sink.

Florentino’s lawyer accused Van Rijswijk of the crime, and a representative of the justice system came to the community. The Dutchman presented himself and denied the accusation. The Defense called the boatmen and the owner of the hotel where they stayed to the stand as witnesses. Van Rijswijk denied that he was there. The case is still under investigation.

“Every parcel of land was selected for its pristine nature, the proximity of navigable rivers, for their protected ports, and for the quality of its beach fronts and views. Caribbean Riviera has already acquired the titles of the majority of the properties in its portfolio. The job of converting lands with“Possession Rights” to “Titled” land is a process excessively complex, that requires significant capital, legal support, logistical capacity and a factor of luck”.

Says the Caribbean Riviera sale´s portfolio.

Based on the findings, what Caribbean Riviera refer to as“luck”, others would call criminal.

Between 2006 and 2016, Max Van Rijswijk registered 16 publicly held companies and 17 foundations in Panama. Carolina Carrizo was the resident agent of seventeen of them. Carrizo was on the Board of Directors of the Ocean Oasis Foundation from its creation, January 9, 2008 until December 29, 2015, when she resigned as the Resident Agent and as a Director.

This foundation, over which presides Van Rijswijk, appears in the Panama Papers, the voluminous documents obtained by the German newspaper, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The information in the Panama Papers is related to a request by the Ocean Oasis Foundation for the adjudication of land. The request was made August 20, 2006 to the Agrarian Reform department of the province of Colón.

According to Public Records and the national archives, Van Rijswijk managed to grab 289 acres across five farms in the Miguel de La Borda community of Donoso district between 2008 and 2013. How much did he payfor these lands? A little more than $700. In this case, he used his lawyers or front men to gain possession rights, then transferred them in a form of a donation to the Ocean Oasis Foundation, property of Max Van Rijswijk. The same one that was found in Panama Papers.

In 2008, he managed to acquire 1,400 acres of land across seven farms under the guise of of seven separate foundations He acquired them for only $3,834. He carried out these transfers in spite of an order by the first Anticorruption Prosecutor of the Attorney General’s Office of Panama to confiscate real estate that was subject to investigation for fraudulent titles that affected, and still affect, dozens of families between Calovébora River and Belén River, in north Veraguas.

They also tried to open an investment fund named Panama Land Fund,under the public limited company name Crownland. The idea was to generate shares to quote on the stock exchange, using the land as backing. The National Securities Commission prohibited the promotion of this fund in order to protect the security of the investors.

Contacting his lawyers is an impossible mission. Their firms’ offices remain unoccupied, like those of lawyer Nelly Perez Arosemena, in the Pancanal of Allbrook Building. Another legal representative of his, Maria Gabriela Reyna Lopez, just got out of prison after having been detained for money laundering. Eugenia Espinoza Arias works today in the city government. She declined to be interviewed when contacted about the case. All of them, in recent times, have resigned from representing the companies.

As if that were not enough, Max Van Rijswijk is in dispute with old partners: he has a committal order for trial in court 14 and an impediment to leave the country. In spite of everything, Van Rijswijk vindicates himself as an honest businessman. "The people who have land that is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars they can read and write, they all who came to my office with a reliable person, we did not buy land from people who did not know they were selling. We paid well at the time and fulfilled all the agreements”, Van Rijswijk defends himself.

For the benefit

of the world

On October 9, 2016, the government requested through the Federal Register that the National Assembly create the National Company of Mineral Resources. This decision shares an intimate strategic link to the advancement of the state’s plan to develop Caribbean land.

According to the National Office of Mineral Resources there are 16 mineral extraction projects approved in the country. Half of them correspond with the area of Donoso and Veraguas, home to one of the largest copper reserves in the world, second only to Chile.

A single project, Minera Panama, is comprised of four zones that add up to 32,124 acres—extraction has just begun, and it promises to earn $200billion in 30 years. The company is making the largest private investment in the history of Panama with more the $6 billion dollars. The Canadian company, First Quantum Minerals, who owns the project, states that Panama’s GDP will increase 4% over the 30 years that their exploitation license will last–and it can be extended for 20 more years. The investment includes their own Caribbean port for direct exportation, and a 300 megawatt carbon-based electric generation plant, which greatly exceeds what is needed for the mine to function. Panama’s capacity to control the royalties and sustainability of the extraction is in dispute.

“In the Atlantic Coast, business companies are behaving as independent republics. In places like Minera Panamá, private business control profit, while local communities receive alegacy of environmental costs ruining their future”.

At the mouth of the Panama Canal in the Atlantic, near the city ofColón, the multinational North American company AES is constructing a 380 megawatt power plant fueled by liquid gas. The Chinese group Shanghai Gorgeous also announced their investment of $1.8 Billion dollars to a new port for shipping containers, as well as another 350 megawatt gas-fueled power plant

To incorporate all of this energy into the national power grid, the government projects the construction of a fourth transmission line that runs along the coast of the Caribbean, connecting Colombia to Costa Rica. This infrastructure will run parallel to the sea and be constructed in conjunction with a road that will unite the new bridge over the Canal with the road to the north of Santa Fe, in Calovébora. And later, it will extend all the way to to Bocas del Toro, where it will meet up with the Italian ENEL’s Fortuna Hydroelectric Plant, AES’s Changuinola 1, and the future Chanquinola 2, which iscurrently under negotiation with a Chinese company.

In Panama there are 71 hydroelectric projects in different phases of development. Ten of them are in Veraguas, including one in Santa Fe, Guayabito. The energy potential of the rivers that flow into the Caribbean make new projects highly likely. In addition, a large wind farm which will occupy more than 2,471 acres inside a National Park is being planned, around Tute Mountain, where Representative Gonzalez managed to title his farm.

In the last ten years, energy consumption in Central America has doubled, and Panama is poised to become the solution to the growth in demand: its immense infrastructure will allow energy exportation to the growing market.

Weeks ago, in their first debate, the National Assembly approved a law that would open up the possibility of selling protected coastal lands in Donoso, on the border of Veraguas, for tourism development. They want to sell the beaches for tourism development. To construct luxury resorts and beach apartments. A fatal blow to the lands and culture of Buglé.

"Beyond the fact that the bill would be of benefit to me, the truth is that a restricted area is not convenient for any of the parties, much less for the locals, who live in poverty", says Van Rijswijk. Palpably, the Conquest of the Atlantic goes beyond the construction of a highway. Five centuries later, it remains the same clash of civilizations: a battle between a way of living on the land and a way of benefiting from that same land.

Credits

Guido Bilbao

Research

Israel Gonzalez

Sol Lauría

Guido Bilbao

Andrea Gallo

Eliana Morales

Data manager

Sol Lauría

Photos and video

Raphael Salazar

Video editing

Lucrecia Caramagna

Design

Tea Alberti

Maps

Rainforest Foundation US.

Copy Editor, English Version

Kamran Rahman

Acknowledgements

Steve Sapienza, Marcelo Larraqui, Rita Vázquez, María Mercedes de Corro y Osvaldo Jordán.

With the support of Rainforest Fundation US, La Prensa newspaper, Connectas and Alianza para la Conservación y el Desarrollo.

This project was supported by

the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Publication date

December 2017

All images are subject to copyright

La Conquista del Atlántico - Spanish Version